[Enjoy this guest post by Ethan Reed, a 2017-2018 graduate fellow as well as a Ph.D candidate in English Literature at the University of Virginia. He came to W&L to give a workshop in Prof. Lesley Wheeler’s ENGL 295_02: African-American Poetry course through a Mellon-funded collaboration with the Scholars’ Lab at UVA. More information about this initiative can be found here. This post is cross-listed on the Scholars’ Lab blog.]

An introductory note: this post offers a rough sketch of the planning that went into, and the ideas that emerged from, a three hour seminar on African American poetry I visited last week taught by Professor Lesley Wheeler at Washington & Lee. As such, it’s pretty long. Feel free to skim or jump around to those sections you’re most interested in! They are (by heading): (1) a brief note on the occasion of me visiting the seminar, (2) how I went about contextualizing Black Arts poetry in an undergraduate seminar setting, (3) insights that emerged from our conversation on Amiri Baraka’s poetry, and (4) how I went about running a brief workshop on machine learning and computational approaches to cultural objects. Enjoy! Plus a huge thank you and shout out to Professor Lesley Wheeler, Mackenzie Brooks, and everyone else at Washington & Lee as well as the Scholars’ Lab that made my visit possible!

(1) The Visit

Last week I had the pleasure of participating in Prof. Lesley Wheeler’s seminar, English 295: African-American Poetry, at Washington & Lee University through a collaboration between the Scholars’ Lab at UVA and W&L. As a part of W&L’s intensive spring semester, this class session clocked in at a solid three hours: we discussed Black Arts poetry, Amiri Baraka in the 1960s, Amiri Baraka in the 2000s, and how to make sense of provocative, overtly political poetry.

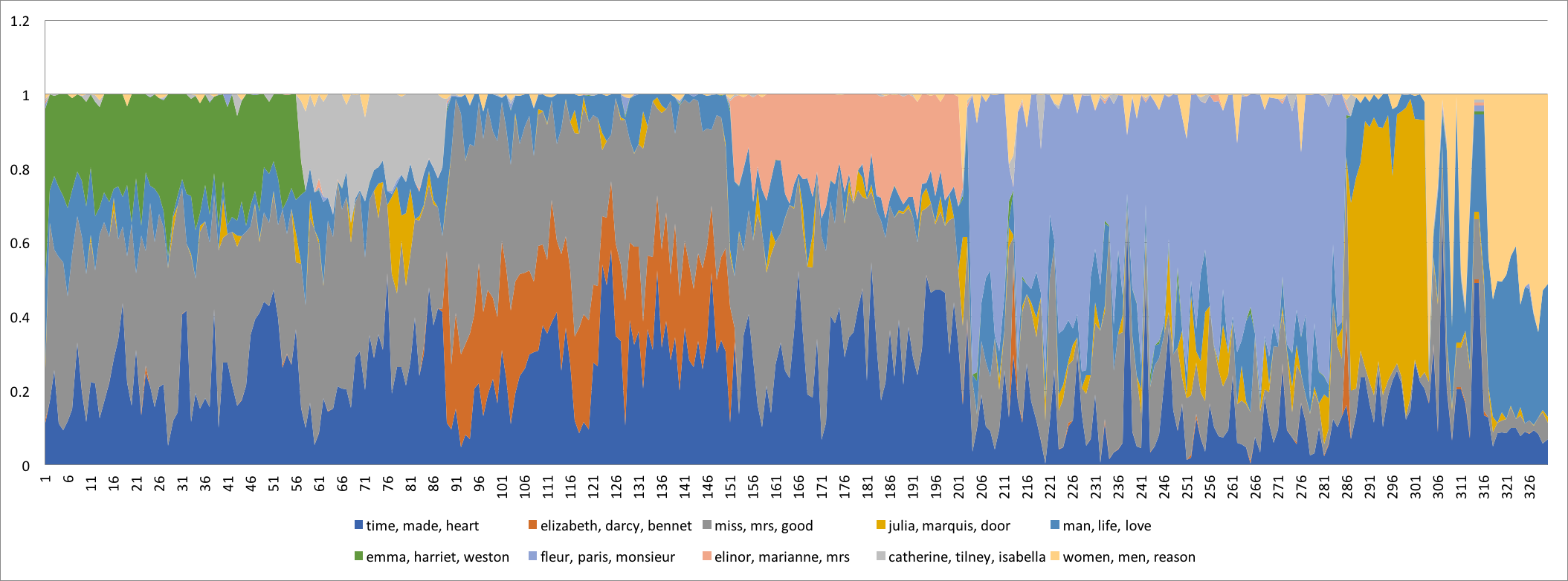

As a PhD candidate in English Literature at UVA, and current Graduate Fellow at the Scholars’ Lab, I study Black Arts poetry. My current project involves using natural language processing techniques like sentiment analysis to analyze and interpret texts from a corpus of Black Arts poetry collections (Baraka included). In particular, I’m interested in digging into how feeling, affect, and sentiment happen in a poem—and how this happening might be coded in terms of race and gender. Part of this includes interrogating the limits of these distanced, potentially decontextualizing computational techniques to think through BAM poetry, and how these methods might best be used to pursue questions, problems, and lines of inquiry centered around black thought and experience.

After initial planning conversations with Prof. Wheeler, we decided it would be most valuable if we combined me presenting on my work with a hands-on workshop on the digital methods I’m using, as well as a more general discussion of how all this might change how we read poems (like those assigned for the class). For structure, we settled on me starting with a brief intro to the Black Arts Movement, followed by a conversation on the assigned readings, then a mini presentation / discussion on my own research that included a full-on participatory workshop on the principles of machine learning, sentiment analysis, and how a sentiment classifier works.

For my presentations and the workshop, I spoke with slides rather than reading from a written out paper. But I still thought it worth sharing how I went about introducing the BAM, conducting a machine learning workshop, and presenting on my own research. So in this post, I’ll give a rough paraphrase of these presentations in addition to insights that emerged from the conversations we had as a class around these issues. As I say in the introductory note—this is a lot! So feel free to jump around.

(2) Contextualizing Black Arts Poetry

After introducing myself to the class, I talked through a handful of slides that I felt offered an engaging introduction to how writers within the Black Arts Movement conceptualized themselves and articulated their artistic, social, and political goals. These are most of the quotations I shared, along with rough paraphrases of how I glossed them with the class:

From Larry Neal, “The Black Arts Movement,” The Drama Review, vol. 12, no. 4 (1968):

“The Black Arts Movement is radically opposed to any concept of the artist that alienates him from his community. Black Art is the aesthetic and spiritual sister of the Black Power concept. As such, it envisions an art that speaks directly to the needs and aspirations of Black America. In order to perform this task, the Black Arts Movement proposes a radical reordering of the western cultural aesthetic. It proposes a separate symbolism, mythology, critique, and iconology.”

To give an example of what this “radical reordering of the western cultural aesthetic” might look like, I shared an image of Sonia Sanchez’s “a/coltrane/poem,” from her 1970 We A BaddDDD People—a poem that, even just glancing at a page, is clearly pursuing a new, radical kind of typography to match its radical aesthetic. (For more on this poem’s indentation, spacing, punctuation, capitalization, and non-traditional spellings, check out my post on transcribing these texts into text editors!). Moreover, this “separate symbolism, mythology, critique, and iconology” included dedicating poems to African American figures like John Coltrane. Sanchez’s “a/coltrane/poem,” then, is one of many Black Arts era poems to take the musician as its main subject matter. Another example of this would be those poems dedicated to Malcolm X—like the 1967 anthology For Malcolm: Poems on the Life and the Death of Malcolm X, edited by Dudley Randall and Margaret G. Burroughs.

From Gwendolyn Brooks’ intro to Don’t Cry, Scream by Haki R. Madhubuti [then Don L. Lee] (1969):

“[Lee] is well-acquainted with ‘elegant’ literature (what hasn’t he read?) but, while certainly respecting the advantages and influence of good workmanship, he is not interested in supplying the needs of the English Departments at Harvard and Oxford nor the editors of Partisan Review … He speaks to blacks hungry for what they themselves refer to as “real poetry.” … Don Lee has no patience with black writers who do not direct their blackness toward black audiences.”

From Haki R. Madhubuti’s Preface to Don’t Cry, Scream (1969):

“What u will be reading is blackpoetry. Blackpoetry is written for/to/about & around the lives/spiritactions/humanism & total existence of blackpeople. … Blackpoetry in its purest form is diametrically opposed to whi-te poetry. Whereas, blackpoets deal in the concrete rather than the abstract (concrete: art for people’s sake; black language or Afro-american language in contrast to standard English, c.). Blackpoetry moves to define & legitimize blackpeople’s reality (that which is real to us).”

I felt these quotations showed how Black Arts writers made the social and political mission behind their work as explicit as possible—that many not only sought to make art that spoke first and foremost to black communities (“Blackpoetry is written for/to/about & around the lives/spiritactions/humanism & total existence of blackpeople”), but felt that the need for this art was urgent, even a kind of imperative (“Lee has no patience with black writers who do not direct their blackness toward black audiences”). Seeing this quotation from Madhubuti’s preface, one of Prof. Wheeler’s students asked a question about why Madhubuti turns the phrases “black poetry” and “black people” into one word—“blackpoetry” and “blackpeople.” I think this is a great question, and my response was mostly that it could mean any number of things depending on context—but that what matters is that we, as readers, pay careful attention to this kind of aesthetic practice (one that includes typographic, linguistic, and conceptual experimentation) and ask questions inquiring into how they might tie into that work’s meaning and potential social practice.

From Amiri Baraka, “An Explanation of the Work.” Black Magic: Sabotage, Target Study, Black Art: Poetry 1961-1967 (1969):

“Sabotage meant I had come to see the superstructure of filth Americans call their way of life, and wanted to see it fall. To sabotage it, I thought maybe by talking bad and getting high, layin out on they whole chorus. But Target Study is trying to really study, like bomber crews do the soon to be destroyed cities. Less passive now, less uselessly ‘literary.’”

Baraka’s poetry was the main subject of Tuesday’s class, so I wanted to give an example of how Baraka himself introduced his work from the 60s in 1969. More specifically, I shared an example of the provocative rhetoric that Baraka has become famous for—what one scholar describes as “a lifetime of saying the unsayable.” Prof. Wheeler’s students had already read several of Baraka’s poems for this class—“Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note,” selections from “Hymn to Lanie Poo,” “A Short Speech to My Friends,” “Three Modes of History and Culture,” “Black Art,” “Black Bourgeoisie,” “Clay,” and “Somebody Blew Up America.” So they had experience with the violence, militancy, and anger behind some of his more incendiary verse. But this quotation, I felt, helped to show how this intensity existed outside of his verse as well—that Baraka would use plain prose in a preface to point his poems like weapons at that “superstructure of filth Americans call their way of life” which “he wanted to see … fall.” The main idea being: it’s not just other people that read Baraka’s poems and interpreted them as militant. Baraka himself framed them as such in introductions to his work.

From Helen Vendler, “Are These the Poems to Remember?” The New York Review of Books, November 24, 2011:

“Rita Dove, a recent poet laureate (1993-1995), has decided, in her new anthology of poetry of the past century, to shift the balance, introducing more black poets and giving them significant amounts of space, in some cases more space than is given to better-known authors. … Dove is at pains to include angry outbursts as well as artistically ambitious meditations.”

“Dove must realize that the new ‘literary standards’ behind this example of Baraka’s verse [“Black Art”] don’t immediately declare themselves. Printing something in short lines doesn’t make the writer a poet; it only makes him a person with a book of short lines. … If one wants evidence of black anger against ‘whitie’ and ‘jewladies’ and ‘mulatto bitches,’ here it is. But a theme is not enough to make a poem.”

From Rita Dove, “Defending an Anthology,” The New York Review of Books, December 22, 2011:

“It is astounding to me how utterly Vendler misreads my critical assessment of the Black Arts Movement, construing my straightforward account of their defiant manifesto as endorsement of their tactics … [she] focuses on that handy whipping boy, Amiri Baraka, plucking passages from his historically seminal poem “Black Art” in which he denigrated Jews, thereby slyly, even creepily implying that I might have similar anti-Semitic tendencies. … I would not have believed Vendler capable of throwing such cheap dirt, and no defense is necessary against these dishonorable tactics except the desire to shield my reputation from the kind of slanderous slime that sticks although it bears no truth.”

These quotations come from an exchange in The New York Review of Books between Helen Vendler, A. Kingsley Porter University Professor at Harvard, and Rita Dove, United States Poet Laureate, Pulitzer Prize winner, and Commonwealth Professor of English at the University of Virginia. The anthology in question is The Penguin Anthology of 20th Century American Poetry, edited by Rita Dove and published in 2011. The issue in question is whether or not poetry by poets like Baraka should appear in it. I give all these details to emphasize that this controversy, who was having it, and where they were having it was—and is—a big deal.

To summarize, Vendler argues that poets like Baraka—whose poetry she characterizes as “angry outbursts,” lacking “literary standards,” and not so much poetry as “a book of short lines”—should not appear in such an anthology at the expense of poets (to cite the examples she gives) like Wallace Stevens and James Merrill. Dove, on the other hand, argues that the “defiant manifesto” of the Black Arts poets matters for our understanding of 20th century American poetry, and deserves to be represented in an anthology claiming to cover that historical and geographical ground.

I included these quotations and this controversy in my introduction to show that, almost fifty years later, Baraka’s poetry still pisses people off. As Dove says in an interview in which she discusses the controversy, this response to certain aspects of Baraka’s poetry makes sense: “No question about it: Amiri Baraka’s ‘Black Art’ is highly problematic in a social sense, a rant with racist, Antisemitic and sexual elements. There’s nothing in this poem I would agree with on a social level … And yet it’s not only a seminal poem of the Black Arts Movement, important for understanding the shock engendered when such indiscriminate rage was thrust into the public, but it is also … a poem that pushes language to despairing extremes and ultimately cracks it open.” Her final comments here, I feel point to another set of problems that professionals, to this day, have with Baraka’s work—a question of whether or not the angry, often militant provocation Black Arts poets made to “literary standards” (what counts as poetry, what aesthetic practices are legitimate, how poems should point themselves toward social or political issues, and so on) should be taken seriously. For Prof. Wheeler’s students, I asked them to consider that if these poems are ruffling feathers in the 2010s, imagine the waves they made in the 1960s during the civil rights movement.

From Ishmael Reed, a 1995 interview quoted in Kalamu ya Salaam, “Black Arts Movement,” in The Oxford Companion to African American Literature (1997):

“I think what Black Arts did was inspire a whole lot of Black people to write. Moreover, there would be no multi-culturalism movement without Black Arts. Latinos, Asian Americans, and others all say they began writing as a result of the example of the 1960s. Blacks gave the example that you don’t have to assimilate. You could do your own thing, get into your own background, your own history, your own tradition and your own culture. I think the challenge is for cultural sovereignty and Black Arts struck a blow for that.”

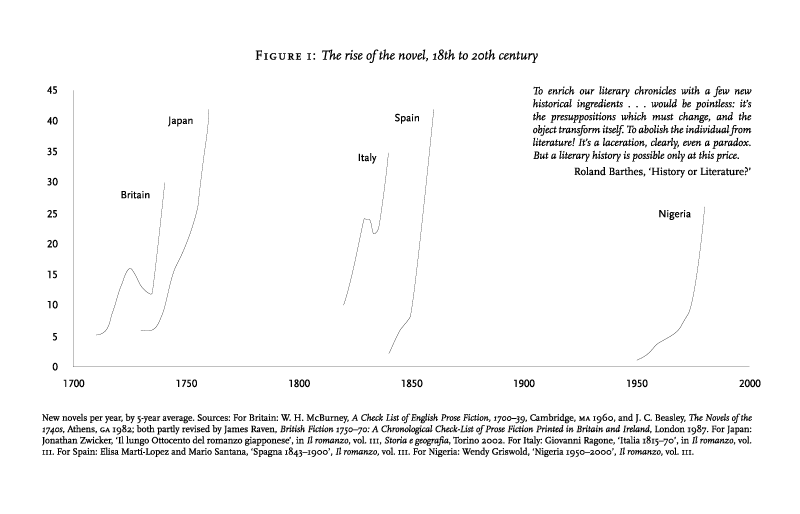

This quotation from The Oxford Companion to African American Literature entry on Black Arts (also available here), I feel, offers a nice birds-eye view on the legacy of the movement. It’s also coming at a slight historical remove—a few decades—and from someone who published poetry during the period but that The Oxford Companion describes as “neither a movement apologist nor advocate” (70). Reed’s connection of Black Arts with multi-culturalism and the idea of “get[ting] into your own background, your own history, your own tradition and your own culture” is a useful one—I think it helps to offer some context on the ripple effects that these artists and their work had on the future of American artistic production. It’s easy to forget and difficult to imagine, I think, how much a political or artistic scene (and the culture associated with it) can change in just a few decades. In the context of a seminar with a broad historical range, hearing Reed reflect on the impact of BAM poetry in this way hopefully helps to bring this historical difference to light.

(3) Class Discussion of Baraka’s Poetry

After this introduction, we turned to the assigned poems by Baraka (“Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note,” selections from “Hymn to Lanie Poo,” “A Short Speech to My Friends,” “Three Modes of History and Culture,” “Black Art,” “Black Bourgeoisie,” “Clay,” and “Somebody Blew Up America”).

Students began by sharing “resonant words” with the whole class—quotations from the readings that resonated with them—after which everyone broke into smaller groups to discuss their choices and why those words in particular stood out. After several minutes, these small groups opened up to the class and kicked off our discussion.

The topics, themes, problems, and passages discussed in the time that followed was genuinely exciting—I had never taught Black Arts poetry before. Though I could anticipate how students might respond to some of these literary texts, I wasn’t sure exactly what to expect. Long story short: I was blown away by the thoughts Prof. Wheeler’s students brought to these texts. In this space here, I want to focus in particular on some of the insights of our discussion of “Somebody Blew Up America,” which many students chose as the subject of their “resonant words” and seemed more generally to spark a great deal of interest for discussion.

To offer some backstory, “Somebody Blew Up America” is one of Baraka’s most infamous poems. Written in the months following 9/11, the poem is a cacophonous, insistent, even hyperbolic interrogation of the “Who” behind various systems of oppression throughout history and across the planet. In discussing the poem’s role “in the business of defining and disrupting what can be said,” one scholar notes the poem’s rhetorical force draws in part from “its torrid mixture of factual, ambiguous, humorous, grotesque, suggestive, and intentionally provocative content” (275). Another scholar describes its “arresting diatribes against the evils of imperialism and the attendant evils of racism” as part of what makes it “an angry poem, perfectly consistent with Baraka’s traditional ‘angry’ persona, fashioned as a response to historical acts of violence caused by imperialist and racist thinking” (464).

The poem became infamous primarily, however, after its performance at the Geraldine Dodge Poetry Festival in September 2002. In particular, critics of the poem cited several lines in which it suggests (by way of asking an unanswered question) that the Israeli government had foreknowledge of the 9/11 attacks. Many charged Baraka with anti-Semitism and called for his removal as poet laureate of New Jersey. Amidst this public outcry, Baraka published a defense of his poem in Counterpunch, titled “The ADL Smear Campaign Against Me” (2002). In the end, unable to remove him from his post as poet laureate, the New Jersey State Senate abolished the post altogether rather than continue to have Baraka fill the position. One scholar cites this controversy as a powerful example of how difficult it is “to read such [political] poetry in an unbiased, informed, appreciative way and how to stay attuned to its aesthetic quality without compromising its ideological potential. In other words, the challenge is how to read overtly political poetry as poetry” (463).

In short: having a conversation about Baraka’s “Somebody Blew Up America” means having a conversation about a whole host of thorny political, social, and artistic issues. The poem is, in a word, provocative—it provokes intense response from its readers. But in the case of Prof. Wheeler’s class, the poem provoked an incredible discussion, parts of which I wanted to highlight here.

The poem’s directness in naming names stood out for many students—from President George Bush to former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice to U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, the poem names the names of those in positions of power as it questions their roles in various systems of oppression. In addition to naming names of the powerful or oppressive, the poem also speaks the names of those killed or harmed while resisting systems of oppression or fighting for social change: from Medgar Evers and Fred Hampton to Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht.

Many students commented on this intensive allusiveness, how the poem pointedly reaches outside of itself and into the world of politics and history. For example, a few noted that the website I had linked for the poem (genius.com, where it is available to read for free) included annotations for many of the poem’s historical references—a textual apparatus several students found extremely helpful in parsing the poem’s external layers of meaning. Prof. Wheeler also noted that the many references in “Somebody Blew Up America” provide it with intellectual heft, as well as evidence of Baraka’s own erudition. Drawing from an earlier discussion on the more canonical literary tradition that Black Arts poets hoped to break from, we also discussed the poem’s resonances with another extremely allusive work (complete with textual annotations): T. S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. But where Eliot invokes Greek myths, Dante Alighieri, and the New Testament, Baraka names current presidents, secretaries of state, and assassinated civil rights leaders. In this sense, we discussed how “Somebody Blew Up America” mobilizes an entirely different audience of readers and for a different purpose, drawing as it does from an entirely different constellation of names, images, myths, and histories.

Students also pointed to the radical rhetorical forms these references took, appearing as they did in rapid fire lists that spanned immense historical and geographical ground in the space of a few clauses. The form of the “list” came particularly into focus after watching a performance of “Somebody Blew Up America” by Baraka in 2009. Almost instantly, students noted a shift in the tone of the poem from its life on the page versus in performance by Baraka with a saxophonist accompanist. The way references unfolded in lists felt qualitatively different: what seemed slower, weightier, and even more solemn on the page felt faster, lighter, or even breezier in performance. Listening to Baraka, there’s no time to satisfy the itch to “get” references by pausing to look them up—as one student noted, Baraka wasn’t waiting around for his listeners: you either got it this time or you didn’t. (Near the end of the performance, Baraka even signals to the saxophonist to speed up, building momentum as he nears the poem’s close).

But rather than feeling overwhelmed, the need to “keep up” with Baraka in performance seemed to change into something else. Drawing from my own listening experience, it felt almost like the particular pacing and affective artistry of Baraka’s performance elaborated on these allusion-rich lists which were themselves shorthand for broader historical perspectives—the idea that, even if you missed the references this time, Baraka’s performance could help, for now, to fill in some of the gaps and to keep you on the same page.

(4) Machine Learning Workshop & My Project

After a brief break following this discussion of Baraka’s poetry, I introduced the class to my project, “Measured Unrest in the Poetry of the Black Arts Movement.” I discussed how I assembled my corpus, how I’m manipulating it to be able to process it with computers, and how I interpret and analyze my results (which I share some of here and here). But before I did any of that, I introduced two concepts central to my research: machine learning and sentiment analysis. In this part of the post, I want to offer a sketch of what that introduction looked like.

Natural language processing, machine learning, sentiment analysis—while extremely important concepts in certain fields, I don’t expect folks in a poetry seminar to have much familiarity with them. So when brainstorming ways to teach these concepts, it felt important for this intro to be hands-on—that is, engaging the class in a participatory way rather than me lecturing—and, for lack of a better word, fun—that is, making concepts that might feel “over someone’s head” instead feel intuitive, exciting, and immediately accessible.

With all this in mind, I decided to make this intro a collective class workshop. My goal was to share the principles behind machine learning processes so that something like sentiment analysis—and what makes it possible—starts to make more sense. So in this workshop, we as a class acted as the “algorithm” in a supervised learning experiment. Our goal was to create a classifier that would guess whether or not a movie is a western based on its movie poster. This took the form of us looking at a whole bunch of movie posters we knew to be westerns and finding patterns in these posters—in this case, identifiable features they had in common. We then tried to generalize from these patterns and guess as a class whether or not a new movie poster was a western. Shout out here to Brandon Walsh, who has used the predictability of movie posters in similar workshops! I have burgled a number of his ideas, with a few key differences—namely that I wanted to push our classifier to the point where its limits became clear and its pre-decided biases or assumptions came to the fore.

We began with our “training data,” several movie posters we already knew to be from westerns. This included classics—Stagecoach, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, The Searchers, High Noon—as well as some later films—A Fistful of Dollars, For a Few Dollars More, Unforgiven, and so on. Our ongoing informal discussion of what patterns we saw in these posters was a lot of fun—one of my goals!—and had the lighter tone I was hoping for. We decided our “algorithm” saw four features in western movie posters: (1) man with hat, (2) man with gun, (3) horses, (4) desert / prairie. Some other features like “damsel in distress” came up, which lead to productive discussions on the differences between what a computer would be good at identifying vs. a human—i.e., that certain features might require levels of interpretive nuance that an algorithm wouldn’t be capable of. More on this in a moment.

With our “classifier” trained, we turned it loose on our “test data”—another set of movie posters, this time with the titles/credits redacted—to see how well it performed. Ideally, the classifier in question would have no foreknowledge of these new inputs (the test data), and would simply perform its classification by rote according to how it was trained (in this case, looking for our four features—hat, gun, horse, dessert/prairie). We would then be able to tell roughly the accuracy of our classifier and tweak it as necessary.

In reality, however, our “classifier” was also a room full of undergraduates already extremely familiar with cinematic genre conventions by virtue of their years of lived experience in a world with movies. So we did our best to “suspend” our far more nuanced human understanding of these movie posters and tried to act instead on our far less nuanced computational decision-making. This is, after all, part of the basic trade-off that computational approaches offer—purchasing the power of automated decision-making and the ability to deal with large corpora at the cost of nuance and complexity.

So, more posters. We started with several our classifier found easy: The Magnificent Seven, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Once Upon a Time in the West, to name a few. Each has hats, guns, horses, and deserts/prairies galore. We then tried more contemporary examples (i.e. The Hateful Eight and Django Unchained) that, while straightforward in terms of how our classifier interpreted their movie posters, started to become more complicated in whether or not they “counted” as westerns.

But my goal with this workshop wasn’t just to give students experience with using a classifier. I also wanted to give them experience with how a computer thinks. This includes the limitations of computational approaches, as well as the ways that initial human biases and assumptions affect seemingly objective algorithmic “results.” So the ambiguous cases of these more modern films started nudging us in that direction. Fortunately for this example of movie posters for westerns, I teach a course on “the western” at the University of Virginia and have some experience with the history, adaptability, and flexible boundaries of this genre (it’s as if I’d been orchestrating it all along!).

So I threw a few curveballs: posters for films like Hud, Brokeback Mountain, There Will Be Blood, and The Revenant—movies that take place in the American west, have themes, imagery, and plots in keeping with more traditional westerns, but also revise or explode the genre in one way or another. This, I tried to emphasize, is where the rubber meets the road in computational analysis. And where all sorts of human, subjective gray areas show up in what may have felt like an objective, algorithm-driven process.

For example, we as human readers might recognize that Leonardo DiCaprio’s snow-crusted beard, long greasy hair, and weathered fur coat on the poster of The Revenant positions the film in a generic tradition defined by rugged individualist heroes and revenge-seeking antiheros struggling against the backdrop of an unforgiving frontier landscape. As thoughtful, human readers, we can also have a conversation about the history of white characters adopting a certain image of Native American culture as they find their place in this “unfamiliar” landscape—an act of appropriation often used to paint their relationship with American soil as non-colonial and “more authentic” as compared with greedy colonialist “bad guys” that they spend the film fighting against, often “on behalf” of Native American communities (more on this in a moment).

But an algorithmic classifier cannot have this conversation. It looks at the input and determines its output according to its training as fast as it possibly can. Pushing this example a little further, I put up the poster for Kevin Costner’s Dances With Wolves. The narrative this film presents—of an alienated white American man being accepted into a Lakota community, then intuitively becoming more skilled at practices associated with this community than its actual members and “inheriting” their culture before they seemingly “vanish”—shows up a lot in stories about the American west (for more on how appropriative, insidious, and ultimately damaging these kinds of narratives are, see a chapter from Louis Owens’ Mixedblood Messages titled “Apocalypse at the Two-Socks Hop: Dancing with the Vanishing American”).

After showing the movie poster for Dances With Wolves—which our “algorithm” did not think was a western—I put up the poster for James Cameron’s 2009 Avatar, a film with an almost identical narrative structure, though instead of the American west it takes place on an alien planet named Pandora, and instead of a Lakota community, the people indigenous to Pandora are a blue alien species called the Na’vi. Judging by its poster, this film looks nothing like a western. Even watching it in theaters, it would be possible to miss ties the film has with a genre that mythologizes the conquest of the American frontier. Talking about the film critically, however, these connections become clear.

So as we tried to decide how our classifier related to these posters, a number of difficult questions arose—can a movie set in space be a western? What even is a western—what does it mean for a film to be part of, or responding to, an established genre? Is it something we can discern from a movie poster in the first place? The answers to these questions—central to the kind of results that a classifier developed through machine learning can provide—are also human decisions, all the way down, made while the classifier is being trained.

Now that the limits and interpretive dangers of computational approaches had taken concrete form, I transitioned to my own use of computational approaches in my research: how I use sentiment analysis (using a classifier to evaluate a given snippet of text for different kinds of sentiment, i.e. “positive” or “negative”)—in my analysis of Black Arts poetry like those that we had spent most of the three hour seminar discussing. Similar questions applied to this research as well: what does it mean for a poem to be “positive” or “negative”? How does a snippet of text “have sentiment” in the first place? How do computational approaches stack up with more traditional ways of reading poetic language for sentiment, feeling, emotion, or affect?

By the time we finished this workshop and I shared how it applied to my own research, we had run out of class-time. Which means, unfortunately, I had to cut an activity I had planned using Prism to “computationally read” Baraka’s poem “Black Art” for political and artistic practice as a class. There’s always more to do and discuss, but what we did discuss felt like an enormous success—by the end of this workshop students seemed to have a strong handle on the principle ideas behind machine learning, as well as how a classifier might be used to analyze different aspects of artistic objects. That, combined with the seriously insightful conversations we’d been having all afternoon, felt like a huge win! So thanks again to Professor Wheeler, Mackenzie Brooks, and everyone else at W&L as well as at the Scholars’ Lab who organized it all and made my whole visit possible.