[Enjoy this guest post by Sam Lemley and Neal Curtis, graduate students in English at University of Virginia. They came to W&L to give a workshop in Prof. Holly Pickett’s sprint-term “Othello, Ourselves: Race, Religion, and Reconciliation in Shakespeare” course through a Mellon-funded collaboration with the Scholars’ Lab at UVA. More information about this initiative can be found here. This post is cross-listed on the Scholars’ Lab blog.]

In some circles, collation is a word to conjure with. While we might all know what it means ‘to collate,’ the practice itself is too often confined to the rarefied world of bibliographical and textual analysis. In consequence, the word has come to connote a dark art. The OED fails to clear things up, telling us only what collation is rather than how it’s done: collation (that subtle science) is the “textual comparison of different copies of a document […] with a view to ascertain the correct text, or the perfect condition of a particular copy.”

During our recent visit to Professor Holly Pickett’s course, “Othello, Ourselves: Race, Religion, and Reconciliation in Shakespeare,” we sought to dispel this obscurantist view of collation. Working with Pickett and her students, we demo’d a suite of digital collating tools and instruments that anyone with a computer, two (or more!) texts to compare, and a little patience can put to use—often with startling results.

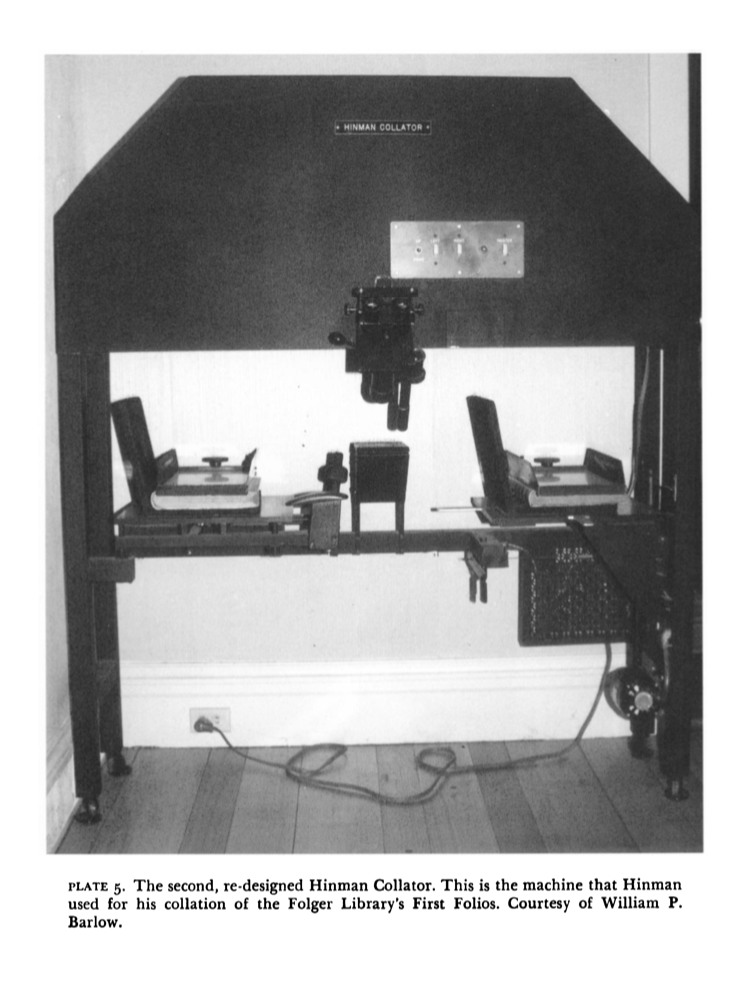

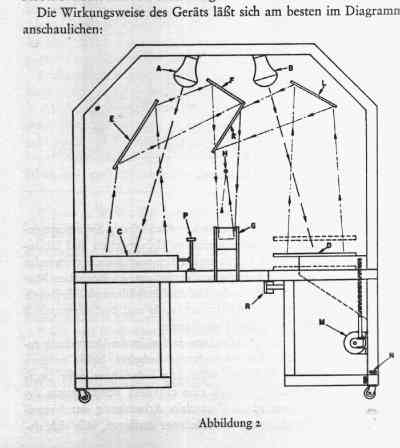

A course on Shakespeare is a fitting (and relatively safe) place to experiment with collation. In the 1940s, UVa graduate student Charlton Hinman developed an optical collating machine to assist in his comparison of extant copies of Shakespeare’s First Folio (1623). In fact, modern techniques of textual collation could be said to originate with Hinman’s work on the first collected edition of Shakespeare’s plays.[1] The eponymous collator that followed Hinman’s early prototyping resembles an electrical ziggurat that (when switched-on) emits clacking sounds and flashes of light. It is, for want of an analogy, kind of like a heavy-metal R2-D2, albeit without the Lucasian droid’s endearing chirps, wobbles, and bloops (see figure, below).

Despite its intimidating aspect, however, in its inventor’s hands the Hinman Collator revealed something incredible: no two copies of the famed First Folio were exactly alike. When examined through the collator’s all-seeing binocular lenses, each copy presented its own assortment of variants—in punctuation, spelling, and even entire lines of speech. These variants offered students and scholars of Shakespeare fresh fodder in the never-ending project of making sense of the inimitable Bard. While the intervening decades have not been kind to Hinman’s invention (approximately fifty-nine Hinman Collators were manufactured; only a few are still operational), optical collation remains an important tool in the textual scholar’s toolkit. {Incidentally, one of the original Hinman Collators is still in use at the University of Virginia.[2] To see it in action (ably demonstrated by fellow UVa English graduate students James Ascher and Ethan Reed), see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AHzn5y4KcJk}

For obvious reasons (its heft and bulk), we could not bring the Hinman Collator with us to Washington & Lee; happily, then, digital humanists have developed a number of text analysis and collation apps that bring robust collational methods to the familiar scale of the personal computer and smartphone. While recent experiments in digital optical collation, including the recently launched ‘PocketHinman’ app, hold promise, in Pickett’s course we decided to focus on the collation of transcribed text—that is, rather than visually comparing two copies of a printed page, we would be comparing raw letters and words, transcribed into easily manipulable .txt files. To do so as a group and to compare our results, we introduced Pickett’s students to an online collation engine called Juxta Commons.

We first asked Pickett’s students to visit juxtacommons.org and create user accounts. That done, we distributed two versions of Act 5, Scene 2 of Othello (a scene Pickett’s students had just read) in .txt format. One version was from the 1622 Quarto printing of the play, the other was from the 1623 First Folio. Though separated by only a single year, these two versions contain one of the most intriguing and complex variants in Shakespeare’s works. The folio reads,

Of one, whose hand

(Like the base Iudean) threw a Pearle away

Richer then all his Tribe.

(V.ii.343-45)

Here Othello (metaphorizing after murdering Desdemona) likens himself to a ‘Judean’. In place of Judean, however, the earlier Quarto reads, Indian. This variant is interesting for a number of reasons, not least because the question of correctness is open to debate. Semantically at least, both ‘Judean’ and ‘Indian’ fit, though each colors Othello’s speech differently: is Othello Jew-like, or like a Native of the ‘New World’? Hence the beauty of these seemingly innocent textual variants; they force us to hold in mind multiple readings simultaneously, deepening our appreciation of the play and Shakespeare’s art. We’ll leave the interpretive heavy-lifting to Pickett’s brilliant students—our demonstration merely aimed to show both the speed with which variants can be detected using Juxta and the value of visualizing these variants with Juxta’s suite of tools. These tools—including theside-by-side viewer, which highlights points of variance between two textual ‘witnesses’, and histogram tool, which visualizes the relative density of variation in each witness—contextualize variants to assist in their interpretation. While discussing why a single word might have changed between the Quarto and Folio, we stressed that Juxta could be used to find similar scholarly cruxes elsewhere. Once found, these cruxes might complicate or add textual depth to students’ readings of a particular moment in any one of Shakespeare’s plays. We also encouraged Pickett’s students to view the words on the pages of their modern editions as the product of recent editorial choice rather than authorial fiat. This kind of textual skepticism—the refusal to take Shakespeare’s heavily-mediated words at face value—can be intimidating. Naturally, students want editorial certainty; they crave the ‘correct’ version to simplify an already complicated text. But textual variability and openness also hold vast promise: the detection of variants and errors reveals something about Shakespeare’s meaning, audience, and culture that modern versions often take pains to cover up. Juxta makes the discovery of these hidden clues easy, even (we think!) fun.

In short, the lesson we hope to have imparted during our time with Pickett’s students is simple: while expertise in Shakespeare’s world and words comes slowly, the familiarity of this technology (particularly to students who navigate web apps with ease) opens new and newly-accessible ways of reading. Reading Shakespeare for the first time can be an exhausting slog through archaic syntax and Elizabethan humor. Juxta and similar tools put the proverbial ball back in the students’ court. We hope, then, that these tools will become increasingly common in literature seminars—their availability spurring students to treat historical texts like datasets ripe for creative recombining and analysis.

We close by thanking Professor Holly Pickett (and her students!) for having us, Brandon Walsh of UVa’s Scholars’ Lab and Sydney Bufkin for facilitating, and the Mellon Foundation, whose grant program for digital humanities made our visit possible. For more information on Juxta—and a more detailed tutorial—see http://juxtacommons.org.

Sam Lemley

Neal Curtis

[1] See Steven Escar Smith, “‘The Eternal Verities Verified’: Charlton Hinman and the Roots of Mechanical Collation,” Studies in Bibliography 53 (2000): 129–61. Hinman estimated that his work on the first folio would have taken decades of constant work without the aid of the Hinman Collator.

[2] For a census of surviving Hinman Collators, see Steven Escar Smith, “‘Armadillos of Invention’: A Census of Mechanical Collators,” Studies in Bibliography 55 (2002): 133–70.