[Crossposted on my personal blog and the Scholars’ Lab blog.]

I’ve accepted a new position as the Head of Graduate Programs in the Scholars’ Lab, and I’ll be transitioning into that role over the next few weeks! As a part of the interview process, we had to give a job talk. While putting together this presentation, I was lucky enough to have past examples to work from (as you’ll be able to tell, if you check out this past job talk by Amanda Visconti). Since my new position will involve helping graduate students through the process of applying for positions like these, it only feels right that I should post my own job talk as well as a few words on the thinking that went into it. Blemishes, jokes, and all, hopefully these materials will help someone in the future find a way in, just as the example of others did for me. And if you’re looking for more, Visconti has a great list of other examples linked from her more recent job talk for the Scholars’ Lab.

For the presentation, I was asked to respond to this prompt:

What does a student (from undergraduate to doctoral levels) need to learn or experience in order to add “DH” to his or her skill set? Is that an end or a means of graduate education? Can short-term digital assignments in discipline-specific courses go beyond “teaching with technology”? Why not refer everyone to online tutorials? Are there risks for doctoral students or the untenured in undertaking digital projects? Drawing on your own experience, and offering examples or demonstrations of digital research projects, pedagogical approaches, or initiatives or organizations that you admire, make a case for a vision of collaborative education in advanced digital scholarship in the arts and humanities.

I felt that each question could be a presentation all its own, and I had strong opinions about each one. Dealing with all of them seemed like a tall order. I decided to spend the presentation close reading and deconstructing that first sentence, taking apart the idea that education and/or digital humanities could be thought of in terms of lists of skills at all. Along the way, my plan was to dip into the other questions as able, but I also assumed that I would have plenty of time during the interview day to give my thoughts on them. I also wanted to try to give as honest a sense as possible of the way I approach teaching and mentoring. For me, it’s all about people and giving them the care that they need. In conveying that, I hoped, I would give the sort of vision the prompt was asking for. I also tried to sprinkle references to the past and present of the Scholars’ Lab programs to ground the content of the talk. When I mention potential career options in the body of the talk, I am talking about specific alumni who came through the fellowship programs. And when I mention graduate fellows potentially publishing on their work with the Twitter API, well, that’s not hypothetical either.

So below find the lightly edited text of the talk I gave at the Scholars’ Lab – “In, Out, Across, With: Collaborative Education and Digital Humanities.” I’ve only substantively modified one piece – swapping out one example for another.

And a final note on delivery: I have heard plenty of people argue over whether it is better to read a written talk or deliver one from notes. My own sense is that the latter is far more common for digital humanities talks. I have seen both fantastic read talks and amazing extemporaneous performances, just as I have seen terrible versions of each. My own approach is, increasingly, to write a talk but deliver that talk more or less from memory. In this case, I had a pretty long commute to work, so I recorded myself reading the talk and listened to it a lot to get the ideas in my head. When I gave the presentation, I had the written version in front of me for reference, but I was mostly moving through my own sense of how it all fit together in real time (and trying to avoid looking at the paper). My hope is that this gave me the best of both worlds and resulted in a structured but engaging performance. Your mileage may vary!

In, Out, Across, With: Collaborative Education and Digital Humanities

It’s always a treat to be able to talk with the members of the UVA Library community, and I am very grateful to be here. For those of you that don’t know me, I am Brandon Walsh, Mellon Digital Humanities Fellow and Visiting Assistant Professor of English at Washington and Lee University. The last time I was here, I gave a talk that had almost exclusively animal memes for slides. I can’t promise the same robust Internet culture in this talk, but talk to me after and I can hook you up. I swear I’ve still got it.

It’s always a treat to be able to talk with the members of the UVA Library community, and I am very grateful to be here. For those of you that don’t know me, I am Brandon Walsh, Mellon Digital Humanities Fellow and Visiting Assistant Professor of English at Washington and Lee University. The last time I was here, I gave a talk that had almost exclusively animal memes for slides. I can’t promise the same robust Internet culture in this talk, but talk to me after and I can hook you up. I swear I’ve still got it.

In the spirit of Amanda Visconti, the resources that went into this talk (and a number of foundational materials on the subject) can all be found in a Zotero collection at the above link. I’ll name check any that are especially relevant, but hopefully this set of materials will allow the thoughts in the talk to flower outwards for any who are interested in seeing its origins and echoes in the work of others.

In the spirit of Amanda Visconti, the resources that went into this talk (and a number of foundational materials on the subject) can all be found in a Zotero collection at the above link. I’ll name check any that are especially relevant, but hopefully this set of materials will allow the thoughts in the talk to flower outwards for any who are interested in seeing its origins and echoes in the work of others.

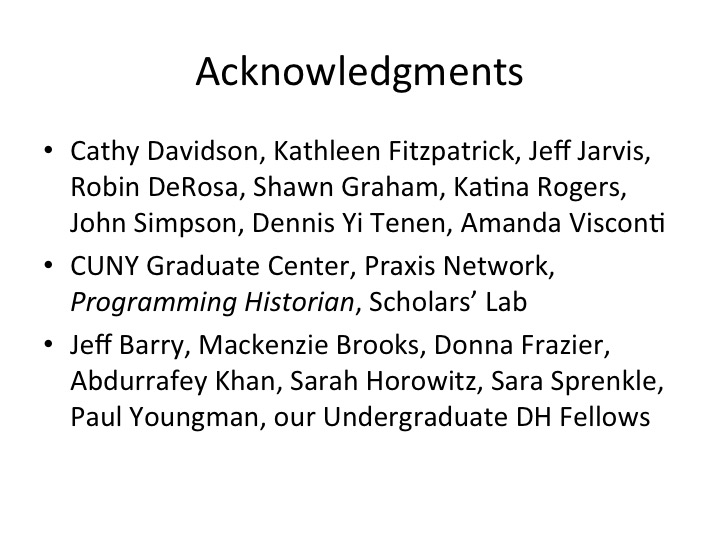

And a final prefatory note: no person works, thinks or learns alone, so here are the names of the people in my talk whose thinking I touch upon as well as just some – but not all – of my colleagues at W&L who collaborate on the projects I mention. Top tier consists of people I cite or mention, second tier is for institutions or publications important to discussion, and final tier is for direct collaborators on this work.

And a final prefatory note: no person works, thinks or learns alone, so here are the names of the people in my talk whose thinking I touch upon as well as just some – but not all – of my colleagues at W&L who collaborate on the projects I mention. Top tier consists of people I cite or mention, second tier is for institutions or publications important to discussion, and final tier is for direct collaborators on this work.

Today I want to talk to you about how best to champion the people involved in collaborative education in digital research. I especially want to talk about students. And when I mention “students” throughout this talk, I will mostly be speaking in the context of graduate students. But most of what I discuss will be broadly applicable to all newcomers to digital research. My talk is an exhortation to find ways to elevate the voices of people in positions like these to be contributors to professional and institutional conversations from day one and to empower them to define the methods and the outcomes of the digital humanities that we teach. This means taking seriously the messy, fraught, and emotional process of guiding students through digital humanities methods, research, and careers. It means advocating for the legibility of this digital work as a key component of their professional development. And it means enmeshing these voices in the broader network around them, the local context that they draw upon for support and that they can enrich in turn. I believe it is the mission of the Head of Graduate Programs to build up this community and facilitate these networks, to incorporate those who might feel like outsiders to the work that we do. Doing so enriches and enlivens our communities and builds a better and more diverse research and teaching agenda.  This talk is titled “In, Out, Across, With: Collaborative Education and Digital Humanities,” and I’ll really be focusing on the prepositions of my title as a metaphor for the nature of this sort of position. I see this role as one of connection and relation. The talk runs about 24 minutes, so we should have plenty of time to talk.

This talk is titled “In, Out, Across, With: Collaborative Education and Digital Humanities,” and I’ll really be focusing on the prepositions of my title as a metaphor for the nature of this sort of position. I see this role as one of connection and relation. The talk runs about 24 minutes, so we should have plenty of time to talk.

When discussing digital humanities education, it is tempting to first and foremost discuss what, exactly, it is that you will be teaching. What should the students walk away knowing? To some extent, just as there is more than one way to make breakfast, you could devise numerous baseline curricula.

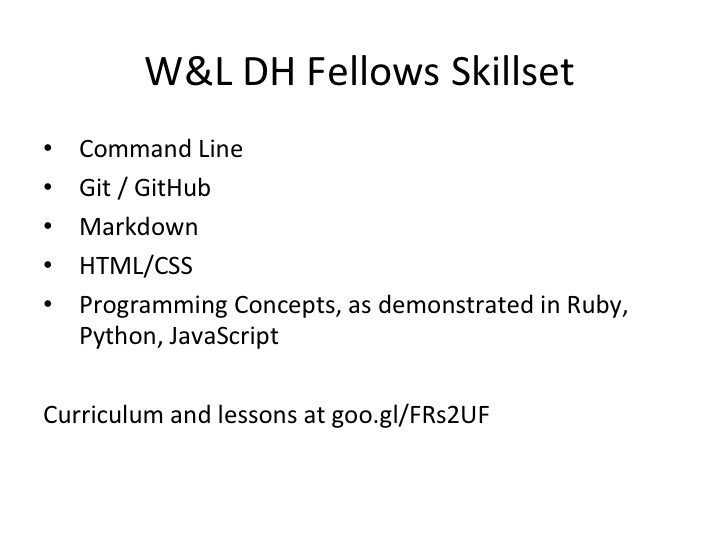

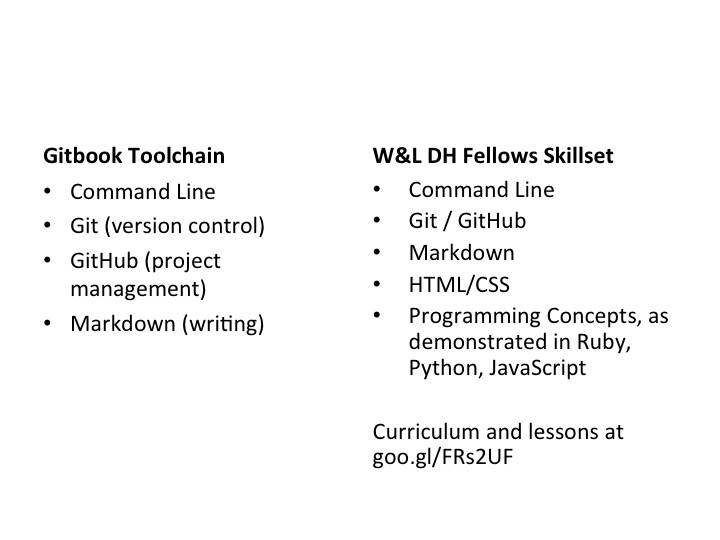

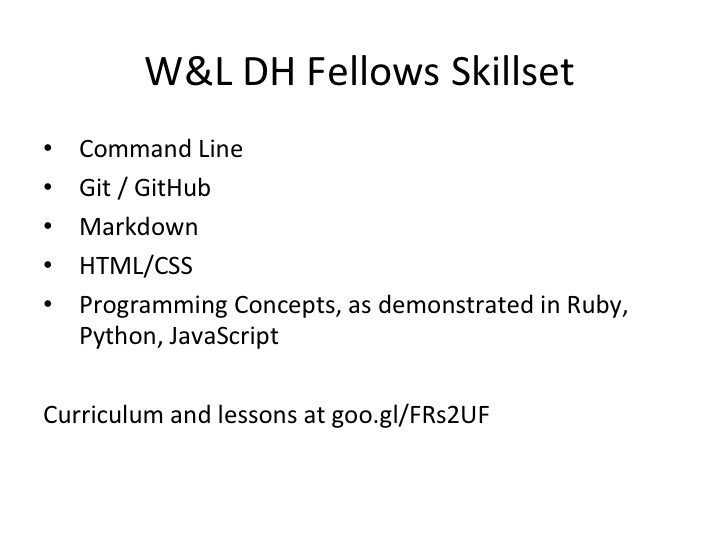

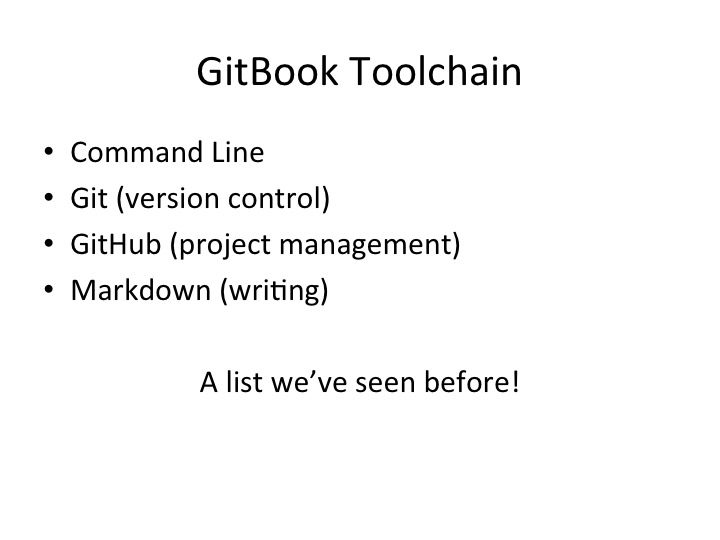

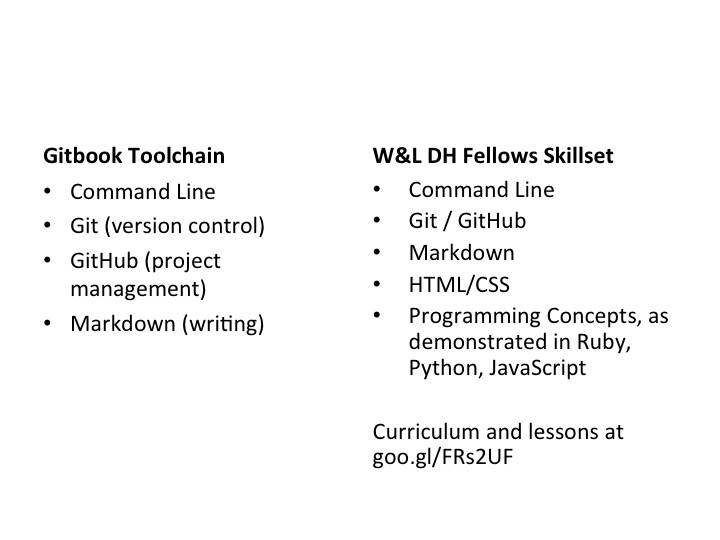

This is what we came up with at Washington and Lee for students in our undergraduate digital humanities fellowship program. We tried to hit a number of kinds of skills that a practicing digital humanist might need. It’s by no means exhaustive, but the list is a way to start. We don’t expect one person to come away knowing everything, so instead we aim for students to have an introduction to a wide variety of technologies by the end of a semester or year. They’ll encounter some technologies applicable to project management, some to front-end design, as well as a variety of programming concepts broadly applicable to a variety of situations. Lists like this give some targets to hit. But still, even as someone who helped put this list together, it makes me worry a bit. I can imagine younger me being afraid of it! It’s easy for us to forget what it was like to be new, to be a beginner, to be learning for the first time, but I’d like to return us to that frame of thinking. I think we should approach lists like these with care, because they can be intimidating for the newcomer. So in my talk today I want to argue against lists of skills as ways of thinking.

I don’t mean to suggest that programs need no curriculum, nor do I mean to suggest that no skills are necessary to be a digital humanist. But I would caution against focusing too much on the skills that one should have at the end of a program, particularly when talking about people who haven’t yet begun to learn. I would wager that many people on the outside looking in think of DH in the same way: it’s a big list of unknowns. I’d like to get away from that.

Templates like this are important for developing courses, fellowship, and degree-granting programs, but I worry that the goodwill in them might all too easily seem like a form of gatekeeping to a new student. It is easy to imagine telling a student that “you have to learn GitHub before you can work on this project.” It’s just a short jump from this to a likely student response – “ah sorry – I don’t know that yet.” And from there I can all too easily imagine the common refrain that you hear from students of all levels – “If I can’t get that, then it’s because I’m not a technology person.” From there – “Digital humanities must not be for me.”

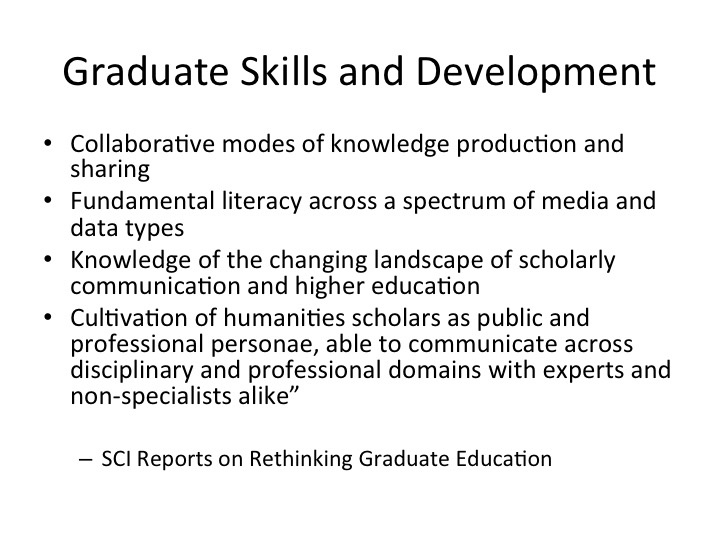

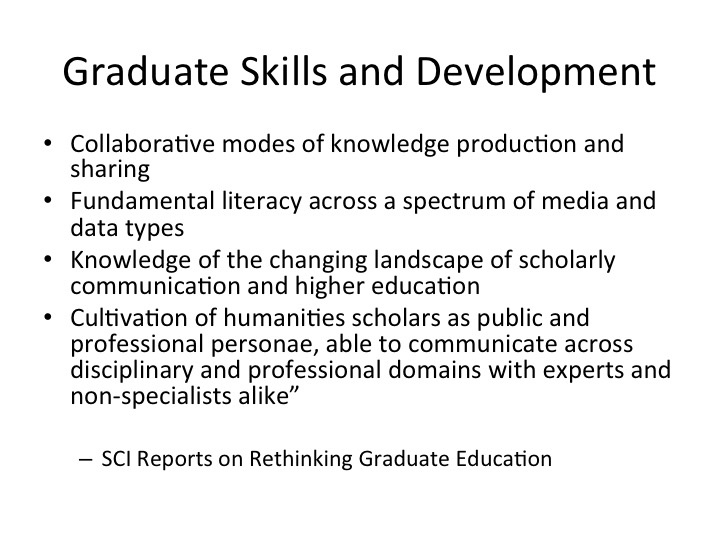

Instead of building our curricula out of as-yet-unknown tool chains, I want to float, today, a vision of DH education as an introduction to a series of professional practices. Lists of skills might be ends but I fear they might foreclose beginnings.  Instead, I will float something more in line with that of the Scholarly Communication Institute (held here at UVA for a time), which outlined what they saw as the needs of graduate and professional students in the digital age. I’ll particularly draw upon their first point here (last of my slides with tons of text, I swear): graduate students need training in “collaborative modes of knowledge production and sharing.”

Instead, I will float something more in line with that of the Scholarly Communication Institute (held here at UVA for a time), which outlined what they saw as the needs of graduate and professional students in the digital age. I’ll particularly draw upon their first point here (last of my slides with tons of text, I swear): graduate students need training in “collaborative modes of knowledge production and sharing.”

I want to think about teaching DH as introducing a process of discovery that collapses hierarchies between expert and newcomer: that’s a way to start. This sort of framing offers digital humanities not as a series of methods one does or does not know, but, rather, as a process that a group can engage in together. Do they learn methods and skills in the process? Of course! Anyone who has taken part in the sort of collaborative group projects undertaken by the Scholars’ Lab comes away knowing more than they came in with. But I want to continue thinking about process and, in particular, how that process can be more inclusive and more engaging. By empowering students to choose what they want to learn and how they want to learn it, we can help to expand the reach of our work and better serve our students as mentors and collaborators. There are a few different in ways in which I see this as taking place, and they’ll form the roadmap for the rest of the talk.  Apologies – this looks like the sort of slide you would get at a business retreat. All the same – we need to adapt and develop new professional opportunities for our students at the same time that we plan flexible outcomes for our educational programs. These approaches are meant to serve increasingly diverse professional needs in a changing job market, and they need to be matched by deepening support at the institutional level.

Apologies – this looks like the sort of slide you would get at a business retreat. All the same – we need to adapt and develop new professional opportunities for our students at the same time that we plan flexible outcomes for our educational programs. These approaches are meant to serve increasingly diverse professional needs in a changing job market, and they need to be matched by deepening support at the institutional level.

So to begin. One of our jobs as mentors is to encourage students to seek out professionally legible opportunities early on in their careers, and as shapers of educational programs we can go further and create new possibilities for them. At W&L, we have been collaborating with the Scholars’ Lab to bring UVA graduate students to teach short-form workshops on digital research in W&L classrooms. Funded opportunities like this one can help students professionalize in new ways and in new contexts while paying it forward to the nearby community. A similar initiative at W&L that I’ve been working on has our own library faculty and undergraduate fellows visiting local high schools to speak with advanced AP computer science students about how their own programming work can apply to humanities disciplines. I’m happy to talk more about these in Q&A.

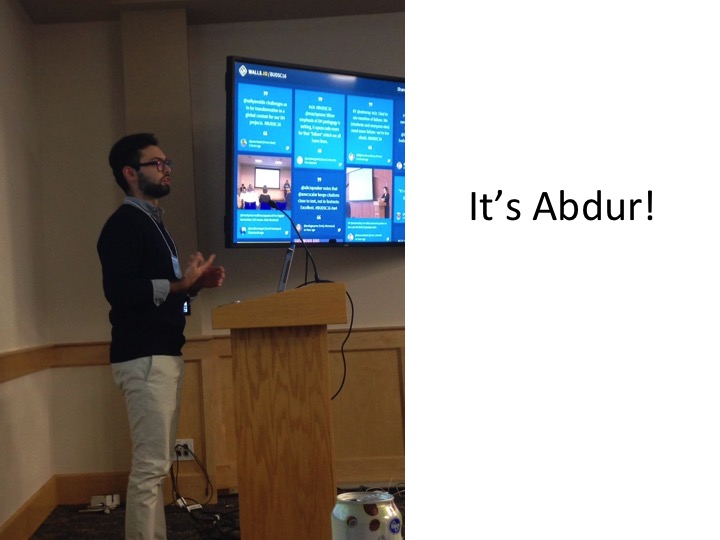

We also have our student collaborators present at conferences, both on their own work and on work they have done with faculty members, both independently and as co-presenters. Here is Abdur, one of our undergraduate Mellon DH fellows, talking about the writing he does for his thesis and how it is enriched by and different from the writing he does in digital humanities contexts at the Bucknell Digital Scholarship Conference last fall. While this sort of thing is standard for graduate students, it’s pretty powerful for an undergraduate to present on research in this way. Learning that it’s OK to fail in public can be deeply empowering, and opportunities like these encourage our students to think about themselves as valuable contributors to ongoing conversations long before they might otherwise feel comfortable doing so.

We also have our student collaborators present at conferences, both on their own work and on work they have done with faculty members, both independently and as co-presenters. Here is Abdur, one of our undergraduate Mellon DH fellows, talking about the writing he does for his thesis and how it is enriched by and different from the writing he does in digital humanities contexts at the Bucknell Digital Scholarship Conference last fall. While this sort of thing is standard for graduate students, it’s pretty powerful for an undergraduate to present on research in this way. Learning that it’s OK to fail in public can be deeply empowering, and opportunities like these encourage our students to think about themselves as valuable contributors to ongoing conversations long before they might otherwise feel comfortable doing so.

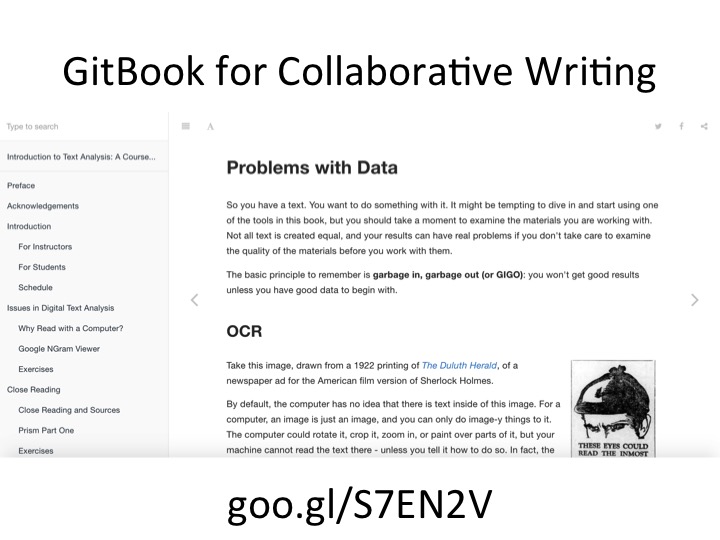

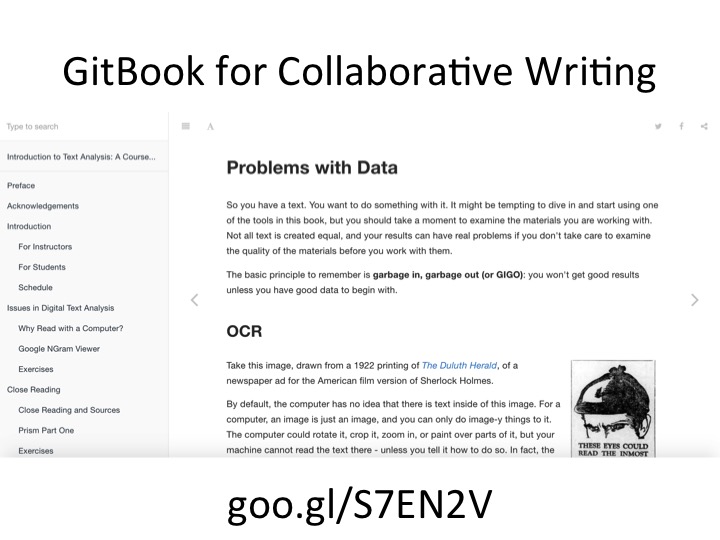

But teaching opportunities and conferences are not the only ways to get student voices out there. I think there are ways of engaging student voices earlier, at home, in ways that can fit more situations. We can encourage students to engage in professional conversations by developing flexible outcomes in which we are equal participants. One approach to this with which I have been experimenting is group writing, which I think is undervalued as a taught skill and possible approach to DH pedagogy. An example: when a history faculty member at W&L approached the library (and by extension, me) for support in supplementing an extant history course with a component about digital text analysis, we could have agreed to offer a series of one-off workshops and be done with it.  Instead, this faculty member – Professor Sarah Horowitz – and I decided to collaborate on a more extensive project together, producing Introduction to Text Analysis: A Coursebook. The idea was to put the materials for the workshops together ahead of time, in collaboration, and to narrativize them into a set of lessons that would persist beyond a single semester as a kind of publication. The pedagogical labor that we put into reshaping her course could become, in some sense, professionally legible as a series of course modules that others could use beyond the term. So for the book, we co-authored a series of units on text analysis and gave feedback on each other’s work, editing and reviewing as well as reconfiguring them for the context of the course. Professor Horowitz provided more of the discipline-specific material that I could not, and I provided the materials more specific to the theories and methods of text analysis. Neither one of us could have written the book without the other.

Instead, this faculty member – Professor Sarah Horowitz – and I decided to collaborate on a more extensive project together, producing Introduction to Text Analysis: A Coursebook. The idea was to put the materials for the workshops together ahead of time, in collaboration, and to narrativize them into a set of lessons that would persist beyond a single semester as a kind of publication. The pedagogical labor that we put into reshaping her course could become, in some sense, professionally legible as a series of course modules that others could use beyond the term. So for the book, we co-authored a series of units on text analysis and gave feedback on each other’s work, editing and reviewing as well as reconfiguring them for the context of the course. Professor Horowitz provided more of the discipline-specific material that I could not, and I provided the materials more specific to the theories and methods of text analysis. Neither one of us could have written the book without the other.

Professor Horowitz was, in effect, a student in this moment. She was also a teacher and researcher. She was learning at the same time that she produced original scholarly contributions. Even as we worked together, for me this collaborative writing project was also a pedagogical experiment that drew upon the examples of Robin DeRosa, Shawn Graham, and Cathy Davidson, in particular.  Davidson taught a graduate course on “21st Century Literacies” where each of her students wrote a chapter that was then collected and published as an open-access book. For us as for Davidson, the process of knowing, the process of uncovering is something that happens together. In public. And it’s documented so that others can benefit. Our teaching labor could become visible and professionally legible, as could the labor that Professor Horowitz put into learning new research skills. As she adapts and tries out ideas, and as we coalesce them into a whole, the writing product is both the means and the end of an introduction to digital humanities.

Davidson taught a graduate course on “21st Century Literacies” where each of her students wrote a chapter that was then collected and published as an open-access book. For us as for Davidson, the process of knowing, the process of uncovering is something that happens together. In public. And it’s documented so that others can benefit. Our teaching labor could become visible and professionally legible, as could the labor that Professor Horowitz put into learning new research skills. As she adapts and tries out ideas, and as we coalesce them into a whole, the writing product is both the means and the end of an introduction to digital humanities.

Professor Horowitz also wanted to learn technical skills herself, and she learned quite a lot through the writing process. Rather than sitting through lectures or being directed to online tutorials by me, I thought she would learn better by engaging with and shaping the material directly. Her course and my materials would be better for it, as she would be helping to bind my lectures and workshops to her course material. The process would also require her to engage with a list of technologies for digital publishing.  Beyond the text analysis materials and concepts, the process exposed her to a lot of technologies: command line, Markdown, Git for version control, GitHub for project management. In the process of writing this document, in fact, she covered most of the same curriculum as our undergraduate DH fellows.

Beyond the text analysis materials and concepts, the process exposed her to a lot of technologies: command line, Markdown, Git for version control, GitHub for project management. In the process of writing this document, in fact, she covered most of the same curriculum as our undergraduate DH fellows.  She’s learning these things as we work together to produce course materials, but, importantly, the technical skills aren’t the focus of the work together. It’s a writing project! Rather than presenting the skills as ends in themselves, they were the means by which we were publishing a thing. They were immediately useful. And I think displacing the technology is helpful: it means that the outcomes and parameters for success are not based in the technology itself but, rather, in the thinking about and use of those methods. We also used a particular platform that allowed Professor Horowitz to engage with these technologies in a light way so that they would not overwhelm our work – I’m happy to discuss more in the time after if you’re interested.

She’s learning these things as we work together to produce course materials, but, importantly, the technical skills aren’t the focus of the work together. It’s a writing project! Rather than presenting the skills as ends in themselves, they were the means by which we were publishing a thing. They were immediately useful. And I think displacing the technology is helpful: it means that the outcomes and parameters for success are not based in the technology itself but, rather, in the thinking about and use of those methods. We also used a particular platform that allowed Professor Horowitz to engage with these technologies in a light way so that they would not overwhelm our work – I’m happy to discuss more in the time after if you’re interested.

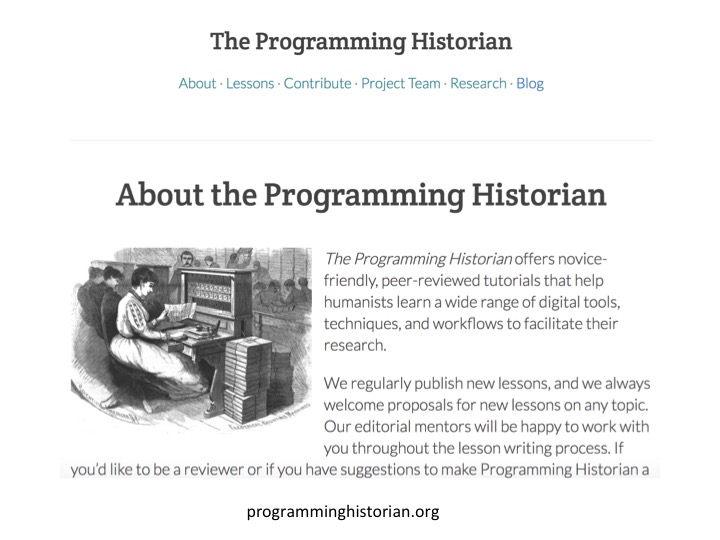

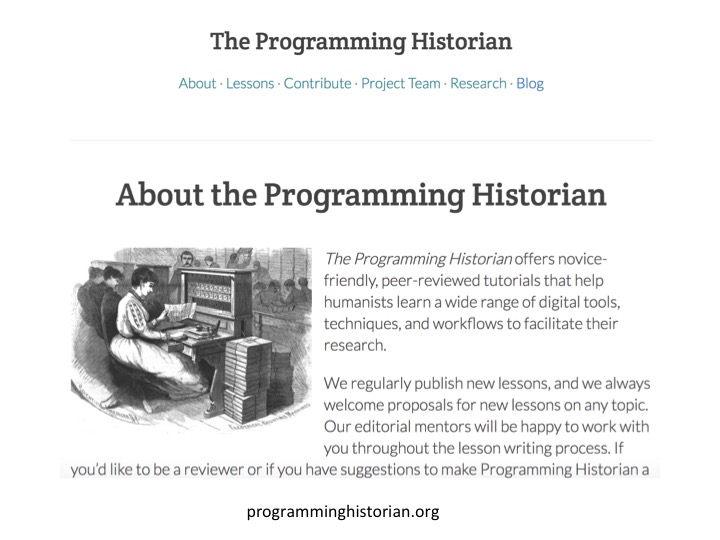

This to say: the outcomes of such collaborative educations can be shaped to a variety of different settings and types of students. Take another model, CUNY’s Graduate Center Digital Fellows program, whose students develop open tutorials on digital tools. Learning from this example, rather than simply direct students or colleagues towards online tutorials like these, why not have them write their own documents, legible for their own positions, that synthesize and remix the materials that they already have found?  The learning process becomes something productive in this framing. I can imagine, for example, directing collaboratively authored materials by students like these towards something like The Programming Historian. If you’re not familiar, The Programming Historian offers a variety of lessons on digital humanities methods, and they only require an outline as a pitch to their editorial team, not a whole written publication ready to go. Your graduate students could, say, work with the Twitter API over the course of a semester, blog about the research outcomes, and then pitch a tutorial to The Programming Historian on the API as a result of their work. It’s much easier to motivate yourselves to write something if you know that the publication has already been accepted. Obviously such acceptance is not a given, but working towards a goal like this can offer student researchers something to aim for. Their instructors could co-author these materials, even, so that everyone has skin in the game.

The learning process becomes something productive in this framing. I can imagine, for example, directing collaboratively authored materials by students like these towards something like The Programming Historian. If you’re not familiar, The Programming Historian offers a variety of lessons on digital humanities methods, and they only require an outline as a pitch to their editorial team, not a whole written publication ready to go. Your graduate students could, say, work with the Twitter API over the course of a semester, blog about the research outcomes, and then pitch a tutorial to The Programming Historian on the API as a result of their work. It’s much easier to motivate yourselves to write something if you know that the publication has already been accepted. Obviously such acceptance is not a given, but working towards a goal like this can offer student researchers something to aim for. Their instructors could co-author these materials, even, so that everyone has skin in the game.

This model changes the shape of what collaborative education can look like: it’s duration and its results. You don’t need a whole fellowship year. You could, in a reasonably short amount of time, tinker and play, and produce a substantial blog post, an article pitch, or a Library Research Guide (more on that in a moment).

As Jeff Jarvis has said, “we need to move students up the education chain.” And trust me – the irony of quoting a piece titled “Lectures are Bullshit” during a lecture to you is not lost on me. But stay with me.

As Jeff Jarvis has said, “we need to move students up the education chain.” And trust me – the irony of quoting a piece titled “Lectures are Bullshit” during a lecture to you is not lost on me. But stay with me.

Collaborative writing projects on DH topics are flexible enough to fit the many contexts for the kind of educational work that we do. After all, no one needs or values the same outcomes, and these shared and individual goals need to be worked out in conversation with the students themselves early on. Articulating these desires in a frank, written, and collaborative mode early on (in the genre of the project charter), can help the program directors to better shape the work to fit the needs of the students. But I also want to suggest that collaborative writing projects can be useful end products as well as launching pads, as they can fit the shape of many careers. After all, students come to digital humanities for a variety of different reasons. Some might be aiming to bolster a research portfolio on the path to a traditional academic career. Others might be deeply concerned about the likelihood of attaining such a position and be looking for other career options. Others still might instead be colleagues interested in expanding their research portfolio or skillset but unable to commit to a whole year of work on top of their current obligations. Writing projects could speak to all these situations.

I see someone in charge of shaping graduate programs as needing to speak to these diverse needs. This person is both a steward of where students currently are – the goals and objectives they might currently have – as well as of where they might go – the potential lives they might (or might not!) lead. After all, graduate school, like undergraduate, is an enormously stressful time of personal and professional exploration. If we think simply about a student’s professional development as a process of finding a job, we overlook the real spaces in which help might be most desired. Frequently, those needs are the anxieties, stresses, and pressures of refashioning yourself as a professional. We should not be in the business of creating CV lines or providing lists of qualifications alone. We should focus on creating strong, well-adjusted professionals by developing ethical programs that guide them into the professional world by caring for them as people.

In the graduate context, this involves helping students deal with the academic job market in particular.  To me in its best form, this means helping students to look at their academic futures and see proliferating possibilities instead of a narrow and uncertain route to a single job, to paraphrase the work of Katina Rogers. A sprinkler rather than a pipeline, in her metaphor. As Rogers’s work, in particular, has shown, recent graduate students increasingly feel that, while they experienced strong expectations that they would continue in the professoriate, they received inadequate preparation for the many different careers they might actually go on to have. The Praxis Program and the Praxis Network are good examples of how to position digital humanities education as answers to these issues. Fellowship opportunities like these must be robust enough that they can offer experiences and outcomes beyond the purely technical, so that a project manager from one fellowship year can graduate with an MA and go into industry in a similar role just as well-prepared as a PhD student aiming to be a developer might go on to something entirely different. And the people working these programs must be prepared for the messy labor of helping students to realize that these are satisfactory, laudable professional goals.

To me in its best form, this means helping students to look at their academic futures and see proliferating possibilities instead of a narrow and uncertain route to a single job, to paraphrase the work of Katina Rogers. A sprinkler rather than a pipeline, in her metaphor. As Rogers’s work, in particular, has shown, recent graduate students increasingly feel that, while they experienced strong expectations that they would continue in the professoriate, they received inadequate preparation for the many different careers they might actually go on to have. The Praxis Program and the Praxis Network are good examples of how to position digital humanities education as answers to these issues. Fellowship opportunities like these must be robust enough that they can offer experiences and outcomes beyond the purely technical, so that a project manager from one fellowship year can graduate with an MA and go into industry in a similar role just as well-prepared as a PhD student aiming to be a developer might go on to something entirely different. And the people working these programs must be prepared for the messy labor of helping students to realize that these are satisfactory, laudable professional goals.

It should be clear that this sort of personal and professional support is the work of more than just one person. One of the strengths of a digital humanities center embedded in a library like this one at UVA is that fellows have the readymade potential to brush up against a variety of career options that become revealed when peaking outside of their disciplinary silos: digital humanities developers and project manager positions, sure, but also metadata specialists, archivists, and more. I think this kind of cross-pollination should be encouraged: library faculty and staff have a lot to offer student fellows and vice versa. Developing these relationships brings the fellows further into the kinds of the work done in the library and introduces them to careers that, while they might require further study to obtain, could be real options.

To my mind the best fellowship programs are those fully aware of their institutional context and those that both leverage and augment the resources around them as they are able. We have been working hard on this at W&L. We are starting to institute a series of workshops led by the undergraduate fellows in consultation with the administrators of the fellowship program. The idea is that past fellows lead workshops for later cohorts on the technology they have learned, some of which we selectively open to the broader library faculty and staff. The process helps to solidify the student’s training – no better way to learn than to teach – but it also helps to expand the student community by retaining fellows as committed members. It also helps to fill out a student’s portfolio with a cv-ready line of teaching experience. This process also aims to build our own capacity within the library by distributing skills among a wider array of students, faculty, and staff. After all, student fellows and librarians have much they could learn from one another. I see the Head of Graduate Programs as facilitating such collaborations, as connecting the interested student with the engaged faculty/staff/librarian collaborator, inside their institution or beyond.

But we must not forget that we are asking students and junior faculty to do risky things by developing these new interests, by spending time and energy on digital projects, let alone presenting and writing on them in professional contexts. The biggest risk is that we ask them to do so without supporting them adequately. All the technical training in the world means little if that work is illegible and irrelevant to your colleagues or committee.  In the words of Kathleen Fitzpatrick, we ask these students to “do the risky thing,” but we must “make sure that someone’s got their back.” I see the Head of Graduate Programs as the key in coordinating, fostering, and providing such care.

In the words of Kathleen Fitzpatrick, we ask these students to “do the risky thing,” but we must “make sure that someone’s got their back.” I see the Head of Graduate Programs as the key in coordinating, fostering, and providing such care.

Students and junior faculty need support – for technical implementation, sure – but they also need advocates – people who can vouch for the quality of their work and campaign on their behalf in the face of committees and faculty who might be otherwise unable to see the value of their work. Some of this can come from the library, from people able to put this work in the context of guidelines for the evaluation of digital scholarship. But some of this support and advocacy has to come from within their home departments. The question is really how to build up that support from the outside in. And that’s a long, slow process that occurs by making meaningful connections and through outreach programs. At W&L, we have worked to develop an incentive grant program, where we incentivize faculty members who might be new to digital humanities or otherwise skeptical to experiment with incorporating a digital project into their course. The result is a slow burn – we get maybe one or two new faculty each term trying something out. That might seem small, but it’s something, particularly at a small liberal arts college. This kind of slow evangelizing is key in helping the work done by digital humanists to be legible to everyone. Students and junior faculty need advocates for their work in and out of the library and their home departments, and the person in this position is tasked with overseeing such outreach.

So, to return to the opening motif, lists of skillsets certainly have their place as we bring new people into the ever-expanding field: they’re necessary. They reflect a philosophy and a vision, and they’re the basis of growing real initiatives. But it’s the job of the Head of Graduate Programs to make sure that we never lose sight of the people and relationships behind them.

Foremost, then, I see the Head of Graduate Programs as someone who takes the lists, documents, and curricula that I have discussed and connects them to the people that serve them and that they are meant to speak to. This person is one who builds relationships, who navigates the prepositions of my title.  It’s the job of such a person to blast the boundary between “you’re in” and “you’re out” so that the tech-adverse or shy student can find a seat at the table. This is someone who makes sure that the work of the fellows is represented across institutions and in their own departments. This person makes sure the fellows are well positioned professionally. This person builds up people and embeds them to networks where they can flourish. Their job is never to forget what it’s like to be the person trying to learn. Their job is to hear “I’m not a tech person” and answer “not yet, but you could be! and I know just the people to help. Let’s learn together.”

It’s the job of such a person to blast the boundary between “you’re in” and “you’re out” so that the tech-adverse or shy student can find a seat at the table. This is someone who makes sure that the work of the fellows is represented across institutions and in their own departments. This person makes sure the fellows are well positioned professionally. This person builds up people and embeds them to networks where they can flourish. Their job is never to forget what it’s like to be the person trying to learn. Their job is to hear “I’m not a tech person” and answer “not yet, but you could be! and I know just the people to help. Let’s learn together.”

It’s always a treat to be able to talk with the members of the UVA Library community, and I am very grateful to be here. For those of you that don’t know me, I am Brandon Walsh, Mellon Digital Humanities Fellow and Visiting Assistant Professor of English at Washington and Lee University. The last time I was here, I gave a talk that had almost exclusively animal memes for slides. I can’t promise the same robust Internet culture in this talk, but talk to me after and I can hook you up. I swear I’ve still got it.

It’s always a treat to be able to talk with the members of the UVA Library community, and I am very grateful to be here. For those of you that don’t know me, I am Brandon Walsh, Mellon Digital Humanities Fellow and Visiting Assistant Professor of English at Washington and Lee University. The last time I was here, I gave a talk that had almost exclusively animal memes for slides. I can’t promise the same robust Internet culture in this talk, but talk to me after and I can hook you up. I swear I’ve still got it. In the spirit of Amanda Visconti, the resources that went into this talk (and a number of foundational materials on the subject) can all be found in a Zotero collection at the

In the spirit of Amanda Visconti, the resources that went into this talk (and a number of foundational materials on the subject) can all be found in a Zotero collection at the  And a final prefatory note: no person works, thinks or learns alone, so here are the names of the people in my talk whose thinking I touch upon as well as just some – but not all – of my colleagues at W&L who collaborate on the projects I mention. Top tier consists of people I cite or mention, second tier is for institutions or publications important to discussion, and final tier is for direct collaborators on this work.

And a final prefatory note: no person works, thinks or learns alone, so here are the names of the people in my talk whose thinking I touch upon as well as just some – but not all – of my colleagues at W&L who collaborate on the projects I mention. Top tier consists of people I cite or mention, second tier is for institutions or publications important to discussion, and final tier is for direct collaborators on this work. This talk is titled “In, Out, Across, With: Collaborative Education and Digital Humanities,” and I’ll really be focusing on the prepositions of my title as a metaphor for the nature of this sort of position. I see this role as one of connection and relation. The talk runs about 24 minutes, so we should have plenty of time to talk.

This talk is titled “In, Out, Across, With: Collaborative Education and Digital Humanities,” and I’ll really be focusing on the prepositions of my title as a metaphor for the nature of this sort of position. I see this role as one of connection and relation. The talk runs about 24 minutes, so we should have plenty of time to talk.

Instead, I will float something more in line with that of the Scholarly Communication Institute (held here at UVA for a time), which outlined what they saw as the needs of graduate and professional students in the digital age. I’ll particularly draw upon their first point here (last of my slides with tons of text, I swear): graduate students need training in “collaborative modes of knowledge production and sharing.”

Instead, I will float something more in line with that of the Scholarly Communication Institute (held here at UVA for a time), which outlined what they saw as the needs of graduate and professional students in the digital age. I’ll particularly draw upon their first point here (last of my slides with tons of text, I swear): graduate students need training in “collaborative modes of knowledge production and sharing.” Apologies – this looks like the sort of slide you would get at a business retreat. All the same – we need to adapt and develop new professional opportunities for our students at the same time that we plan flexible outcomes for our educational programs. These approaches are meant to serve increasingly diverse professional needs in a changing job market, and they need to be matched by deepening support at the institutional level.

Apologies – this looks like the sort of slide you would get at a business retreat. All the same – we need to adapt and develop new professional opportunities for our students at the same time that we plan flexible outcomes for our educational programs. These approaches are meant to serve increasingly diverse professional needs in a changing job market, and they need to be matched by deepening support at the institutional level. We also have our student collaborators present at conferences, both on their own work and on work they have done with faculty members, both independently and as co-presenters. Here is Abdur, one of our undergraduate Mellon DH fellows, talking about the writing he does for his thesis and how it is enriched by and different from the writing he does in digital humanities contexts at the Bucknell Digital Scholarship Conference last fall. While this sort of thing is standard for graduate students, it’s pretty powerful for an undergraduate to present on research in this way. Learning that it’s OK to fail in public can be deeply empowering, and opportunities like these encourage our students to think about themselves as valuable contributors to ongoing conversations long before they might otherwise feel comfortable doing so.

We also have our student collaborators present at conferences, both on their own work and on work they have done with faculty members, both independently and as co-presenters. Here is Abdur, one of our undergraduate Mellon DH fellows, talking about the writing he does for his thesis and how it is enriched by and different from the writing he does in digital humanities contexts at the Bucknell Digital Scholarship Conference last fall. While this sort of thing is standard for graduate students, it’s pretty powerful for an undergraduate to present on research in this way. Learning that it’s OK to fail in public can be deeply empowering, and opportunities like these encourage our students to think about themselves as valuable contributors to ongoing conversations long before they might otherwise feel comfortable doing so. Instead, this faculty member – Professor Sarah Horowitz – and I decided to collaborate on a more extensive project together, producing

Instead, this faculty member – Professor Sarah Horowitz – and I decided to collaborate on a more extensive project together, producing  Davidson taught a graduate course on “21st Century Literacies” where each of her students wrote a chapter that was then collected and published as an open-access book. For us as for Davidson, the process of knowing, the process of uncovering is something that happens together. In public. And it’s documented so that others can benefit. Our teaching labor could become visible and professionally legible, as could the labor that Professor Horowitz put into learning new research skills. As she adapts and tries out ideas, and as we coalesce them into a whole, the writing product is both the means and the end of an introduction to digital humanities.

Davidson taught a graduate course on “21st Century Literacies” where each of her students wrote a chapter that was then collected and published as an open-access book. For us as for Davidson, the process of knowing, the process of uncovering is something that happens together. In public. And it’s documented so that others can benefit. Our teaching labor could become visible and professionally legible, as could the labor that Professor Horowitz put into learning new research skills. As she adapts and tries out ideas, and as we coalesce them into a whole, the writing product is both the means and the end of an introduction to digital humanities. Beyond the text analysis materials and concepts, the process exposed her to a lot of technologies: command line, Markdown, Git for version control, GitHub for project management. In the process of writing this document, in fact, she covered most of the same curriculum as our undergraduate DH fellows.

Beyond the text analysis materials and concepts, the process exposed her to a lot of technologies: command line, Markdown, Git for version control, GitHub for project management. In the process of writing this document, in fact, she covered most of the same curriculum as our undergraduate DH fellows.  She’s learning these things as we work together to produce course materials, but, importantly, the technical skills aren’t the focus of the work together. It’s a writing project! Rather than presenting the skills as ends in themselves, they were the means by which we were publishing a thing. They were immediately useful. And I think displacing the technology is helpful: it means that the outcomes and parameters for success are not based in the technology itself but, rather, in the thinking about and use of those methods. We also used a

She’s learning these things as we work together to produce course materials, but, importantly, the technical skills aren’t the focus of the work together. It’s a writing project! Rather than presenting the skills as ends in themselves, they were the means by which we were publishing a thing. They were immediately useful. And I think displacing the technology is helpful: it means that the outcomes and parameters for success are not based in the technology itself but, rather, in the thinking about and use of those methods. We also used a  The learning process becomes something productive in this framing. I can imagine, for example, directing collaboratively authored materials by students like these towards something like

The learning process becomes something productive in this framing. I can imagine, for example, directing collaboratively authored materials by students like these towards something like  As Jeff Jarvis has said, “we need to move students up the education chain.” And trust me – the irony of quoting a piece titled “Lectures are Bullshit” during a lecture to you is not lost on me. But stay with me.

As Jeff Jarvis has said, “we need to move students up the education chain.” And trust me – the irony of quoting a piece titled “Lectures are Bullshit” during a lecture to you is not lost on me. But stay with me. To me in its best form, this means helping students to look at their academic futures and see proliferating possibilities instead of a narrow and uncertain route to a single job, to paraphrase the work of Katina Rogers. A sprinkler rather than a pipeline, in her metaphor. As Rogers’s work, in particular, has shown, recent graduate students increasingly feel that, while they experienced strong expectations that they would continue in the professoriate, they received inadequate preparation for the many different careers they might actually go on to have.

To me in its best form, this means helping students to look at their academic futures and see proliferating possibilities instead of a narrow and uncertain route to a single job, to paraphrase the work of Katina Rogers. A sprinkler rather than a pipeline, in her metaphor. As Rogers’s work, in particular, has shown, recent graduate students increasingly feel that, while they experienced strong expectations that they would continue in the professoriate, they received inadequate preparation for the many different careers they might actually go on to have.  In the words of Kathleen Fitzpatrick, we ask these students to “do the risky thing,” but we must “make sure that someone’s got their back.” I see the Head of Graduate Programs as the key in coordinating, fostering, and providing such care.

In the words of Kathleen Fitzpatrick, we ask these students to “do the risky thing,” but we must “make sure that someone’s got their back.” I see the Head of Graduate Programs as the key in coordinating, fostering, and providing such care. It’s the job of such a person to blast the boundary between “you’re in” and “you’re out” so that the tech-adverse or shy student can find a seat at the table. This is someone who makes sure that the work of the fellows is represented across institutions and in their own departments. This person makes sure the fellows are well positioned professionally. This person builds up people and embeds them to networks where they can flourish. Their job is never to forget what it’s like to be the person trying to learn. Their job is to hear “I’m not a tech person” and answer “not yet, but you could be! and I know just the people to help. Let’s learn together.”

It’s the job of such a person to blast the boundary between “you’re in” and “you’re out” so that the tech-adverse or shy student can find a seat at the table. This is someone who makes sure that the work of the fellows is represented across institutions and in their own departments. This person makes sure the fellows are well positioned professionally. This person builds up people and embeds them to networks where they can flourish. Their job is never to forget what it’s like to be the person trying to learn. Their job is to hear “I’m not a tech person” and answer “not yet, but you could be! and I know just the people to help. Let’s learn together.”